Henry A. Thiede

Recently I received an inquiry about Henry Thiede, an early member of the P&C (born 1871, member as of about 1906). Unfortunately, in my research, I haven't found the answer to the particular question posed.

But I did learn about Henry Thiede, who was president of the club in 1923. (Thiede has appeared before on this blog--he travelled in Europe with Hake in 1912-13 and his photo appeared in the 1943 newspaper article about the club.)

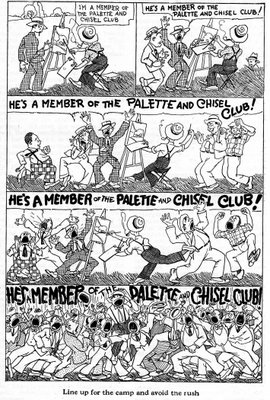

Art director of the Red Book Corporation, Thiede was also the publisher of the club newsletter. He put out the newsletter ten months of the year from 1924 to 1932. In that year, publication ceased on account of the Depression. This was truly an amazing labor of love, especially when one considers that Thiede made of the newsletter much more than the usual circular of club gossip. Someday I will return to that subject in a longer post about the newsletter.

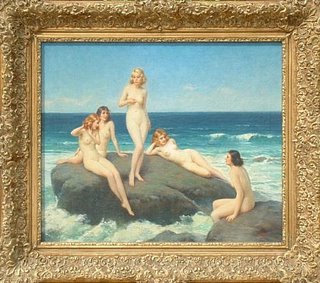

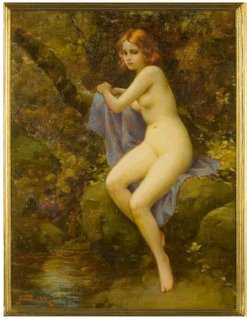

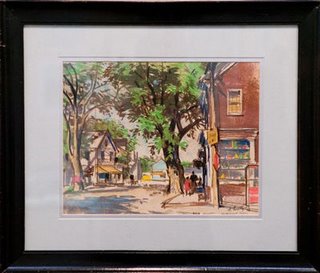

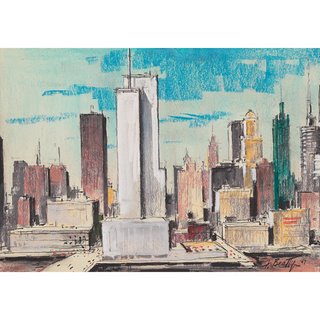

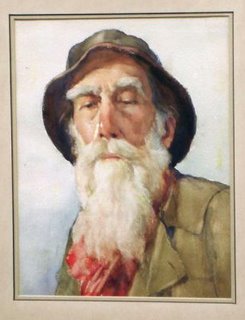

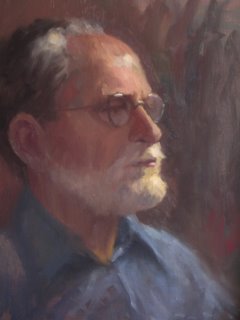

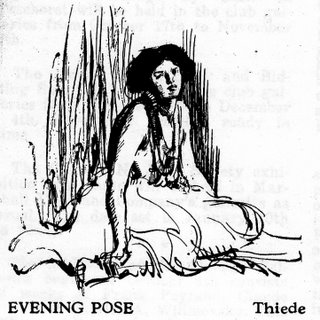

In the January 1926 number, Thiede reproduced a drawing done by one of the members (I believe it was his) "from a model recently posed in the club studio for the evening class. It is our intention to print similar reproductions from time to time, not only to embellish our columns, but to show the members who seldom use the studio that something is going on there all the time." All of the drawings here are atributed to Thiede himself.

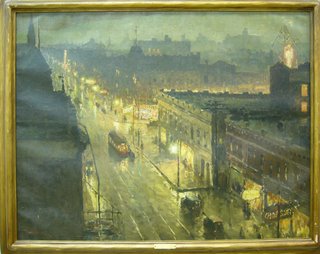

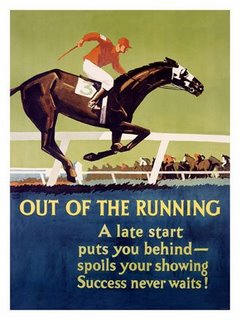

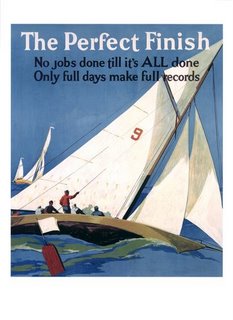

Thiede went on to do illustrations for such publications as the Blue Book of Fiction and Adventure in October 1938 and February 1939.

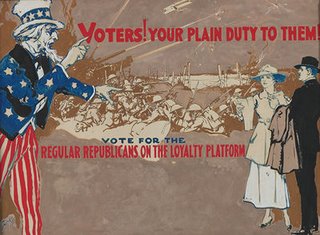

Thiede went on to do illustrations for such publications as the Blue Book of Fiction and Adventure in October 1938 and February 1939.I also found this poster by Thiede, which I would guess was done for the election of 1918 but is as timely now as it was then: